Today’s Random Topic

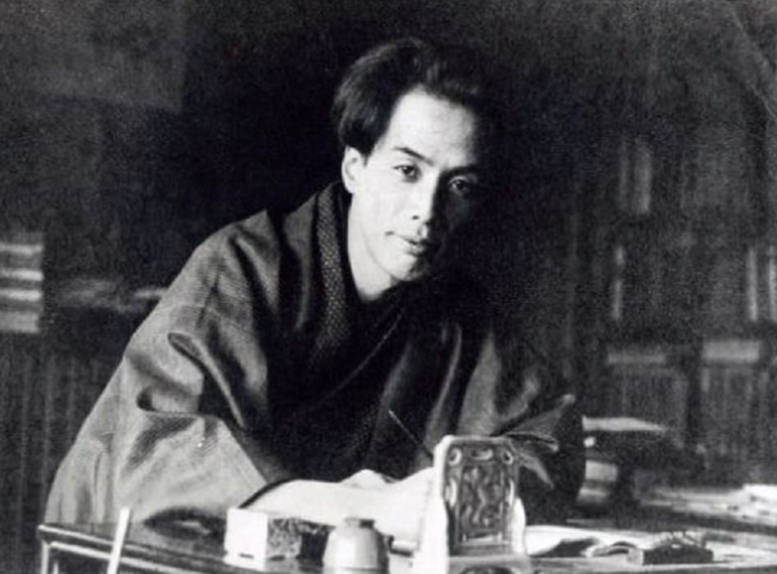

「地獄(じごく)の話が多いー芥川龍之介」

“Many hell stories – Ryunosuke Akutagawa”

Keywords

精神(せいしん)に異常(いじょう)をきたす – to have mental illness

神経(しんけい)を病む(やむ) – to have mental illness (nerve illness)

自殺未遂 (じさつみすい )– attempted suicide

睡眠薬 (すいみんやく )– sleeping pills

悪(あく) – evil

飢饉(ききん) – starvation

自然災害 (しぜんさいがい )– natural disaster

病気(びょうき)の感染 (かんせん )– pandemic (disease spreading)

解雇(かいこ) – lose job

遺体(いたい) – deal body

老婆(ろうば) – old woman

かつら – wig

正当化(せいとうか) – justified

干物(ひもの) – dried

餓死(がし) – die from hunger

Please do not read the English translation if you would like to do “Listening Challenge”!

芥川龍之介は日本の作家で、夏目漱石の弟子の一人です。

Ryunosuke Akutagawa is a Japanese writer and one of Soseki Natsume’s apprentice.

彼は1892年に生まれました。

He was born in 1892.

七ヶ月の時に母親が精神に異常をきたしたため、叔父の芥川の家に引き取られました

When he was seven months old, his mother had mental issues, so his uncle took him in.

彼も大学の専攻は夏目漱石のように英文学科でした。

His major in college was English literature like Soseki Natsume.

そのためか、彼の作品は構成がイギリス文学的だと言われています。

It is said that his writing style is more British.

彼も30歳ごろに神経を病み始めました。

He started experiencing mental illness when he was around 30 years old.

太宰治じゃないですが、彼も秘書と自殺未遂を起こしました。その時は亡くなりませんでしたが、のちに大量の睡眠薬を飲んで自殺しました。

Though he is not Osamu Dazai, he tried to commit double suicide with his secretary. They did not die at the time, though, Akutagawa committed suicide by overdosing on sleeping pills.

彼の有名な作品は、「蜘蛛の糸」「地獄変」と、いろいろありますが、地獄みたいな怖い話が多いです。

There are many popular stories such as The Spider’s Thread or Hell Screen that are scary stories about the hell.

私は日本文学専攻だったので彼の話をたくさん読みましたが、怖かったです。

Since my major was Japanese literature, I read many of his scary stories.

羅生門は黒澤明も映画化して1951年にアメリカのアカデミー賞もとった有名な話なので、今日はその話をしたいと思います。”

Today, I would like to talk about Rashomon that became a film directed by Akira Kurosawa that won an Academy Award in the USA in 1951.

羅生門は1915年に書かれた小説で、テーマは「生きるための悪」についてです。

Rashomon was written in 1915, and the theme is “Evil to live.”

夏目漱石の「心」では、「人はいざという時に急に悪人に変わるから恐ろしい」という落胆の気持ちが書かれていますが、こちらは、「生きるために悪は仕方ない」というテーマですね。

話の背景は平安時代(794年から1185年)、飢饉や自然災害が続き、人々は食べるものもなく、病気の感染も拡大していた。

It takes place during the Heian era (from 794 to 1185) when a series of pandemics and natural disasters occurred and people did not have food to eat so disease spread.

そのため、人々の心は荒(すさ)んでいき、誰も人を信じることができなくなっていった。

Therefore, people started carrying a callous heart that could not trust others.

主人公の男も仕事を解雇され、食べることもできないので、強盗になろうとするが、そんな勇気も出なかった。

The main character, “A man,” lost his job and could not eat, so he tried becoming a thief though he did not have the courage.

途方に暮れて、羅生門を歩いていると、門の二階でいくつもの遺体が捨てられているのを見つけた。

He felt lost and was walking around Rasho gate where he found many dead bodies lying on the second floor.

そこに、老婆が若い女の遺体から髪を抜いてかつらを作ろうとしていた。

There, an old woman was trying to make wigs by pulling out hair from the dead bodies of young woman.

男は、老婆がしていることに腹がたって、刀を抜いた。

The man was upset when he saw it and pulled out his sword.

しかし老婆は自分の行為を正当化した。

However, the old woman justified her action.

「死体から抜いた髪でかつらを作ることは悪いことだろう。だが、それは自分が生きるための仕方のない行為だ。ここにいる死人も生きている時には同じことをしていた。

“I know it’s not good behavior to make a wig using the hair pulled from a dead body. However, there is no way other to live. These dead people used to do similar things when they were alive.

この死んだ女も、生きている時には蛇の干物を、魚の干物と嘘をついて売り歩いていた。それは生きるために仕方がなく行(おこな)った悪だ。

This dead woman used to sell dried snake while saying it’s dried fish. However, it’s the necessary evil in order to live.

だから自分が髪を抜いても、この女は私を許すだろう。」

So she would forgive me even though I am pulling out her hair.

男は老婆の言葉を聞いて勇気が生まれる

He felt courage by listening to her words.

そして老婆をおし倒して着物をはぎ取り、「俺もそうしなければ、餓死をする体なのだ。」と言い残 し、去った

Then he pushed the old woman, took her clothing and left there after saying, “If I did not do this, I would die from hunger.

自分だったら、どうしますか〜!?

What would you do if it were you?!

静かに死んでいきますか?それとも、強盗になりますか?

Are you going to die quietly, or would you become a thief?

自分が親だったら、子供を守らないといけないしね!

If you had children, you have to protect them!

とりあえず私は、住むところも食べるものもある今の日本に感謝します。

Anyways, I am grateful that I have place to live and food to eat in Japan today.

P8 会話文1 (Dialogue) 質問をする・聞き返す

モニカ: はじめまして。私は文学を専攻しているモニカ・ウエストと申(もう)します。

Monica: How do you do? I’m Monica West and I’m majoring in literature. I’m here today to ask you some questions.

今日は、先生に色々教えていただきたいと思います。どうぞよろしくお願いいたします。

Could you please help me? (Please don’t be hard on me.)

森田: こちらこそ。よろしく。

Morita: The pleasure is mine (same here)

モニカ: まず、先生のご専門の昔話について、お聞きしたかったんですが。。。

Monica: First of all, I’d like to ask you about your area of specialty: folk tales.

森田: ええ、いいですよ。どうぞ。

Morita: Certainly. Go ahead.

モニカ: 日本にはたくさん昔話があるそうですが。。。

Monica: I’ve heard that there are many folk tales in Japan.

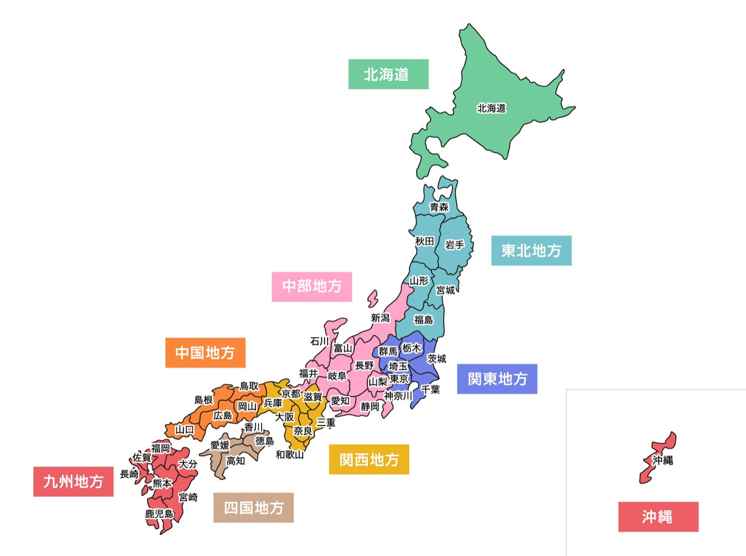

森田: ええ、地方によって色々な昔話がありますよ。

Morita: Yes, there are various folk tales from each chiho (Region).

モニカ: 先生、「地方」という言葉はときどき聞きますが、田舎(いなか)のことですか?

Monica: Professor, I sometimes hear the word chiho, does it mean “rural areas”?

森田: 田舎という意味もありますが、その他に関東地方とか関西地方のように使うこともあります。

Morita: It can mean rural areas, but we also use it as in Kanto chiho or Kansai chiho.

モニカ: 「関東地方」というのは、東京のことですか?

Monica: Does Kanto chiho mean Tokyo?

森田: いえ、東京だけでなく、横浜とか千葉とか東京の周りの場所も入ります。

Morita: No, not just Tokyo, but also the areas around Tokyo, such as Yokohama and Chiba.

「関西地方」だったら、大阪や京都や神戸やその周りですね。

Kansai chiho refers to Osaka, Kyoto, Kobe, and their surrounding areas.

モニカ: そうですか。昔話はどんな内容が多いんですか?

Monica: I see. What are most folk tales about?

森田: そうですね。その地方の名所や地名や名物に関係がある話が多いですね。

Morita: Well, let me see. There are a lot of stories related to famous places, place names, and local specialties of the region.

それから、伝統的な行事とかも。

Also, things such as dentoteki na gyoji (traditional events).

モニカ: あのう、すみません、伝統??って何ですか?もう一度おっしゃっていただけませんか?

Monica: Um, what is “dento”? Could you please repeat it?

森田: ああ、伝統的な行事って言ったんですよ。行事というのは、年や季節で決まった時に特別に何かを行うことです。

Morita: Oh, I said “dentoteki na gyoji”. Gyoji (event) means “something special people do during a particular time of year or season.”

それから、「伝統的」というのは、「昔からある」という意味です。

And , “dentoteki” (traditional) means, “events existing from a long time ago”.

だから、「伝統的な行事」というのは、「昔からあるイベント」ということですね。

So “dentoteki na gyoji” means “events existing from a long ago”.

モニカ: そうですか。じゃ、お正月は伝統的な行事なんですか?

Monica: I see. Well then, does that mean that New Year’s is a traditional event?

森田: はい、もちろんです。ひな祭りや子供の日や七夕も伝統的な行事ですよ。

Morita: Yes, of course. There are also Hinamatsuri (Doll’s festival), Kodomo-no-hi (Children’s Day), and Tanabata (Star Festival).

モニカ: そうですか。分かりました。昔話は名所や地名に関係があるとおっしゃいましたけれど、そういう話はその地方の人たちしか知 らないんですか?

Monica: I see. I understand. You said that folk tales are related to famous sites and place names, but are the stories known only to people from those regions?

森田: いえ、そんなことはありません。一般的に知られている話もたくさんあります

Morita: No, not necessary. There are many commonly-known stories as well.

例えば、「桃太郎」とか、「鶴の恩返し」とか。

For example, Momotaro and Tsuru no Ongaeshi.

モニカ: あ、桃太郎は紙芝居で見たことがあります。歌も歌えます。

Monica: Oh, I’ve seen the story of Momotaro as a kamishibai (a story told through pictures). I can sing the song too.

「ももたろさん、ももたろさん」

“Momotaro-San, Momotaro-San. ”

森田: そうですか。モニカさんも知っていますか。日本の子供達は、紙芝居とか 絵本で昔話を覚えるんですよ。

Morita: Oh, really? You know it, too? Japanese children learn towards tales through kamishibai and picture books.

モニカ: 私はもっと色々な昔話が知りたいです。

Monica: I’d like to know more folk tales.

森田: じゃ、インターネットで調べてみたらどうですか? 色々なサイトが絵やマンガと一緒に昔話を紹介していて楽しいですよ。

Morita: Well then, why don’t you try looking folk tales up on the Internet? There are various websites that introduce folk tales through pictures or comics, and they are a lot of fun.

モニカ: はい、そうしてみます。先生、今日は、色々教えていただいてありがとうございました。大変勉強になりました。

Monica: Yes, I’ll try that. Thank you for telling me about so many things today. I learned a lot.

森田: いいえ、どういたしまして。何か知りたいことがあったら、また来てください。

Morita: You’re welcome. Please come again if there’s anything else you’d like to know.

モニカ: はい、今日は本当にありがとうございました。失礼(しつれい)します。

Monica: Yes, thank you very much. Please excuse me.

内容質問

1)モニカさんの専攻は何ですか?森田先生の専門は何ですか?

2)二人は、「地方」という言葉にはどんな意味があると言っていますか。

3)関東地方と関西地方は、どこにありますか?4ページの地図で探して、県の名前も行ってみましょう。

4)昔話には、どんなことに関係がある話が多いですか?

5)紙芝居は、どんなものだと思いますか。紙芝居を見たことがありますか?

答え)Answer

1)モニカさんの専攻は何ですか?森田先生の専門は何ですか?

モニカさんの専攻は、文学です。森田先生の専門は、昔話です。

2)二人は、「地方」という言葉にはどんな意味があると言っていますか。

地方という言葉には、田舎という意味だけでなく、関東地方や関西地方のように、〇〇地方という意味でも使われます。

3)関東地方と関西地方は、どこにありますか?4ページの地図で探して、県の名前も行ってみましょう。

4)昔話には、どんなことに関係がある話が多いですか?

その地方の名所や地名とか、名物や伝統的な行事とかに関係がある話が多いです。

5)紙芝居は、どんなものだと思いますか。紙芝居を見たことがありますか?

自由回答

Kamishibai is a form of Japanese street theatre and storytelling that was popular during the Depression of the 1930s and the post-war period in Japan until the advent of television during the twentieth century.

<質問の仕方>

質問をする。

Polite to casual

紙芝居についてお聞きしたいんですが。。。(お聞きする)

I would like to ask you about ~

(Casual)

紙芝居のことを聞きたいんだけど。。。

紙芝居のことを聞いていい?

紙芝居ってなに?

(Polite)

紙芝居について伺いたいんですが。。。(伺う)

紙芝居についてお聞きしてもよろしいでしょうか?(お+stem+する)

紙芝居について伺ってもよろしいでしょうか? (teform +も よろしいでしょうか)

紙芝居について、お伺いしてもよろしいでしょうか?(二重謙譲語)

Humble language is used for “My action related to my boss, strangers or older people (someone not your friends or family)”. The sentence implies “My rank is lower than you.”

私は上司から仕事をいただいた。

I received a job from my boss.

上司「日本からのお土産のクッキーだよ。食べて」These are souvenir cookies. Please have some.

花子「一つ、いただきます。ありがとうございます。」I will have one. Thank you very much.

(Someone who eat the cookie is me, lower ranked person. Higher ranked person gave me a cookie, then I, lower ranked person, described my action related to higher ranked person.)

「お伺いする」

(1)聞く・訪問する → 伺う(謙譲語)

(2)お〜する→ お聞きする(聞くの謙譲語)

(3)(1)+(2) お伺いするーdouble 謙譲語

(1)These are special humble verbs

聞く・訪問するー伺うー伺います

食べる・飲むーいただくーいただきます

言うー申すー申します

行く・来るー参るー参ります。

いるーおるーおります

するーいたすーいたします

あるーござるーございます

〜ているー〜ておる。ー〜ております

〜です。ー〜でござるー〜でございます。

You need to memorize these, however, other than these verbs, we use “お+stem + する”

(2)お〜する

会うー お 会い する

お stem する

(3)For 伺う, we combine (1) and (2), and makes the expression even more polite

お伺いする

This is the special case

We don’t say, ”おいただきする” or ”お申しする”